God the Son: The Scapegoat

Michael A Rizzotti

A logical sequence to the essay God the Father brings us to the person of Jesus Christ although the concept of the Incarnation is not present in the Old Testament since any image of God is forbidden. As we have said, in Judaism the name of Yahweh is so sacred that it is not even uttered. And even though the Old and the New Testaments appear incompatible in view of this conflicting and fundamental issue, the Gospels advocate and describe a transition between the old tradition and a new one. The New Testament inaugurates an-other religious reality: that of the Son of God, the Word Incarnate.

A logical sequence to the essay God the Father brings us to the person of Jesus Christ although the concept of the Incarnation is not present in the Old Testament since any image of God is forbidden. As we have said, in Judaism the name of Yahweh is so sacred that it is not even uttered. And even though the Old and the New Testaments appear incompatible in view of this conflicting and fundamental issue, the Gospels advocate and describe a transition between the old tradition and a new one. The New Testament inaugurates an-other religious reality: that of the Son of God, the Word Incarnate.

The word Gospel is a derivative of godspel, meaning “good tidings”. The original word in Greek meant “the good news” translated from the Hebrew word bissar, meaning “herald of good tidings” or “to bring the good news of salvation”.1

None of the authors of the Gospels knew or met Jesus. Their personal account of the life of Jesus is nonetheless a revelation of their own faith in Christ. Unlike the Pentateuch, each Gospel is written by a single author. They were in all likelihood written between 60 and 90 CE.

The core of the narratives that relates the life of Jesus is made up of the three synoptic Gospels. These accounts are called synoptic because they share a common perspective; they are the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. The fourth one, the Gospel of John, does not share the same chronology of Jesus’ life.2 Matthew and Luke have a richer material than Mark, and although they complement each other, they also differ in many important facts.

We will not debate here the synoptic problem of the parallels and incongruities between the texts. Instead we will focus on the fundamental themes and chronology of Jesus’ life.

In accordance with tradition, the Gospel of Matthew begins with the genealogy of Joseph, Jesus’ legal father. This most important theme of the Bible is carefully perpetuated in the first narrative. From Adam, to “the generations of Adam”, to Noah, to Shem, and to Abraham, etc…3 The evangelist establishes Joseph as the legal heir to the Fathers. Notwithstanding that Jesus is not Joseph’s biological son but his legal one.

Among the ancestors enumerated in the genealogy are the names of four women: Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, and Bathshebah (Uriah’s wife). One explanation for their presence in a patriarchal lineage is perhaps to make a connection between Mary’s virginal conception and the irregular nature of the union of these women with their own partners.4 For instance, Tamar took the initiative in her scandalous union with Judah. Rahab had been a prostitute but she nevertheless made it possible for Israel to enter the promised land. Ruth was responsible for an irregular union with Boaz without which there may not have been a Davidic line. And finally Uriah’s wife, Bethshebah, had an affair with David that resulted in the birth of Solomon.

In post-biblical Jewish piety, the circumstances surrounding these unconventional events were seen as the work of the Spirit of God. All these examples show the unfathomable and intriguing nature of God’s intervention in human affairs as a way to influence the course of history.

*

In Matthew, the dreams of Joseph are paralleled with Joseph (in Genesis) whose ability to read dreams brought his people into Egypt and saved them from famine. Joseph, in the New Testament, also has dreams where God tells him to flee to Egypt in order to save Jesus from the murderous hands of Herod. By bringing Jesus to Egypt, he providentially relives the experience of the people of Israel.5

Biblical typology

Old Testament sequence:

Joseph’s dreams bring his people to Egypt and save them from famine

Moses escapes from the wicked hands of the Pharaoh.

Moses delivers his people out of Egypt to the promised land.

Moses wanders forty years in the desert.

New Testament sequence:

Joseph’s dreams bri ng his family to Egypt and savehis child from Herod

Jesus escapes from the hands of the wicked Herod

Joseph leaves Egypt and comes back to Galilee

Jesus fasts forty days in the desert

As soon as the Pharaoh dies, Moses is able to return safely to Egypt. Likewise, Jesus is able to return to Nazareth as soon as Herod dies. Upon Jesus’ return from Egypt, he relives the Exodus and the coming to the promised land.

Moses’ untimely death unable him to see the promised land and the journey is completed by Joshua. The name Jesus is a nickname of Joshua. The analogy and symbolism underlined by the typologies are insightful.

The Evangelists describe the link between the Old tradition and the New. Moses didn’t live to see the promised land, Joshua did. Therefore, when Mary is told to call her son Jesus -Joshua- a new quest for the promised land has begun.

In the beginning of his journey Jesus is first led away from Bethlehem, the city of David, the King of Jews, and brought back to Galilee, the land of the Gentiles. He takes up residence in Nazareth where he begins his mission and becomes known as Jesus the Nazarene. Here the Gospels have taken up the difficult task of reconciling the Old tradition with the New in announcing the “good news” to all the people, Jews and Gentiles alike.

Jesus’ identity is best related to in terms of his relationship with his God/Father and the world. He described himself as a spiritual physician, a shepherd to his people, a divinely authorized prophet. Foremost, Jesus calls himself the Son of man. This latter epithet may have been used by Jesus as a way to describe himself simply as someone in the quality of a human being. He also described his God simply as abba or “dear father”, or dad. In this sense the relationship between him and his Father is a very personal and intimate one.

*

During Pompey’s conquest of Jerusalem in 63 BCE, the priests ruled Israel. It was under the control of the Roman emperors Anthony and Octavian that the reign of Herod the Great began (37-4 BCE). Herod was known to be tyrannical yet competent. He was subservient to Rome but harsh and violent with his people. At his death he divided his kingdom among his three sons. Rome, however, did not confer upon them the title of king. The kingdom of Judaea and the title of ethnarch was bestowed to Archelaus. The kingdom of Galilee and Perea was given to Antipas, also known as Herod the tetrarch whom Jesus called “that fox”: the one who executed John the Baptist. And finally, the north-eastern territory of the Sea of Galilee, was given to Philip with the title of tetrarch also. Of all the three sons, Archelaus was most like his father, except that he was more violent and less competent. For that reason, representatives of the Jewish aristocracy went to Rome to complain about the despotic ruler hoping that Rome would allow them to reinstate a Jewish theocracy. Augustus recognized their plea and banished Archelaus from his office but put Judaea under the status of a third-class province governed by a procurator appointed by Rome.

At that time, the territory of Judea, especially Jerusalem, was the center of Jewish worship. Jerusalem, more precisely its temple, was believed to be the heart of true Judaism. The territory outside it was considered to be unclean and impure. This was particularly the case of neighboring Galilee which was made up of a Jewish and non-Jewish population of Syrians and Greeks, still heavily influenced by Hellenism.6

The change in the political status of Judea also meant that it had to pay its taxes directly to Rome. This enraged a number of Jewish people because it was considered sacrilegious to pay tribute directly to a foreign and heathen ruler. To appease the Jews, and as a gesture of good will, Augustus decreed that synagogues were inviolable and Jews were to be exempt from appearing in court on their Sabbath.7

It was because of the foreign collection of these taxes that Judas the Galilean led a Jewish revolt against Rome in 6 CE. Although the uprising was firmly suppressed, the seeds of discontent were rooted among the radicals of the land. Rebellious ideals were further fomented by a group of Zealots that kept the spirit of revolt alive for the next two generations.

The peaceful coexistence between the procurators and the high priests went on more or less smoothly inasmuch as the high priests continued to pay the Roman representatives bribes to keep their office. It was a practice that accommodated the priests and enriched the procurators. It is not surprising that under these circumstances the high-priesthood had lost the respect of the population. Only the richest priestly families were able to retain their sacred office. Such was the case of Joseph Caiaphas (18-36 CE) who managed to keep his office despite the nomination of Poncius Pilate (26-36 CE). These arrangements, however, did not guarantee a good relationship between Rome and Judea.

It turned out that Poncius Pilate had an uncanny ability to offend Jewish susceptibility. On one occasion, in an act of deliberate spite, he had put a dedication to the Emperor on Herod’s palace. The Jewish elite was greatly insulted by it. They soon sent a deputation to Tiberius to complain about the emblem. They argued that the procurator had not put his name on the Jerusalem’s palace to honor him but simply to annoy them. Tiberius in a gesture of good will ordered the shields to be taken down.

Although Rome was firmly in control of Judaea, it shared some of its power with the clerical elite as a peaceful accommodation. The Pharisees, the Sadducees, and the Essenes, were among the priestly schools of thought ─haeresis─ which began to flourish during the Hasmonean resistance (167-164 BC).

The Pharisees believed in the written laws of Moses, but contrary to the Sadducees and the Essenes, they also believed in the oral laws handed down to them by the Fathers. They believed in the resurrection of the body for the good soul, and eternal damnation for the wicked. The name Pharisees is derived from the Greek translation of the Hebrew perushim meaning separatists, deviants, or heretics. They were called so because these people were so scrupulous about the laws and rituals that they separated themselves from the less observant masses, the ‘ammei ha-arets.8

The Sadducees were the other major group of priests that flourished in Jerusalem during Jesus’ life. They claimed to be the direct descendants of Zadok, the high priest in Solomon’s temple. They were called tseduquim. Contrary to the Pharisees, they believed that only the written laws were to be observed. This brought the Pharisees and the Sadducees in bitter conflict. In addition, the Sadducees did not share the Pharisees’ belief in the immortality of the soul nor did they believe in the resurrection of the body. Despite all their differences, they managed to coexist and the two groups shared their priestly duties in the temple. The most notorious Sadducee is Caiaphas, the high priest who took part in Jesus’ trial.

The Pharisees had come to formulate a doctrine of the two realms: render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s and unto God what is God’s. In accordance to this doctrine the Pharisees tolerated that the people paid their taxes to Rome. It permitted a compromise in matters regarding the state, as long as it did not interfere with their religious affairs.

But the compromise was seen by the more radical groups as an act of treason. A group of these revolutionaries, called the Fourth Philosophy, gave the Romans and Jewish collaborators a hard time until they all committed suicide in the fortress of Masada in 73 CE.

Among the many priestly characteristics that are severely criticized by Jesus in the narrative is their scrupulous and hypocritical application of the law. The overwhelming preoccupation with purity and reward supplanted a simple and unadorned piety. The conscientious concern with legal requirements mostly void of any inward religious feelings transformed the ethical into the judicial: the moral and religious were replaced by the legal and formal. In other words, the Spirit of the law was replaced by the letter of the law and by endless litigation.

Pharisees/scribes

sacred/law vs profane/common

pietists vs masses

pure vs impure

clean vs unclean

Every single aspect of the historical, political, economical, social, and religious context in which Jesus Christ lived and died is important. Every one of these factors help to understand the development of events that led to the culmination of Jesus Christ.

As we will see, the miracles are the clearest signs of Jesus’ earthly activity. They delineate whom Jesus privileged with his presence. The miracles are the signs that separate those who were metamorphosed by his message and those who opposed it. Among his opponents were the priests and the religious elite of Jerusalem.

The Gospels recount Jesus’ mission among the people, who for the most part were outcasts. The narratives show that he directed the attention on them by performing his miracles. The narratives describe these miracles as signs.9 The narratives also use the words mighty deeds, and manifestations of power. The term power here should be understood in the sense of Jesus’ active presence among the outcasts who have no rank or standing among the principalities and powers of this world. The miracles are meant to point out the significant social condition in which the outcasts live. In this context the miracles are a banner that circumscribe Jesus’ ministry.

In the Old Testament the sign is used as the invisible active power of God. The book of Genesis shows how numerous symbols of nature are used to emphasize the sacred events in history. Similarly, in Genesis the sun and the moon are signs -symbols- for seasons, days and years, the circumcision, a sign of the covenant (Gen. 17:10), and the sign of blood on the door in Exodus heralds the pass over (Ex. 12:13). God uses signs as symbols to indicate his will to the hearer.

Isa. 7:13 And he said , “Hear then, O house of David! Is it too little for you to weary men, that you weary my God also? Therefore the lord himself will give you a sign. Behold, a young woman (or virgin) shall conceive and bear a son and shall call his name Imman’u-el.”10

*

The first miracle related in the Gospels of Matthew and Luke is the virginal conception. The quote of Isaiah above is an important parallel that links the virginal birth of Jesus to the Old Testament. Throughout the narratives the Evangelists take a great deal of care in legitimizing Jesus as the Messiah prophesied in the Bible. The reason for such a concern becomes clearer as Jesus is confronted by accusations from the religious elite about his origins and authority. Not only does Jesus come from Galilee, the land of the aliens and heathens, but he arrogantly questions the honesty of the priesthood. They, in return, challenge the origin of his power to perform miracles since only God can perform miracles.11

We have talked about the miracles as signs that circumscribe Jesus’ message of faith. The physical account of the cures, the exorcisms, the raising of the dead, the multiplication of the breads, all point to a violation of the laws of nature. Since all four Evangelists, each in their own way, confirm the reality of the physical aspect of the miracles in the narrative, it is impossible to fully elucidate their reality. Although the mystery involving their physical nature and origin may not be explained, these signs point to the whole purpose of Jesus’ ministry rather than the mysterious origin of his powers. In this sense, he uses the miracles to direct the attention toward a certain category of people, who for the most part, are segregated by society. His aim is to circumscribe the alien and marginal side of the religious reality.

types of miracles

1) the healings: sick, lepers, handicapped

2) exorcisms: casting out demon and evil spirits

3) feeding the hungry and poor

4) raising the dead

5) calming the storm, changing the water into wine

who benefits from the miracles

1) the forgotten: the sick, the poor, and the hungry

2) the outcasts: the lepers, the possessed

3) the helpless: the handicapped, the dead

4) the foreigners: Romans, strangers, pagans

5) the outsiders: the women, the children

If we take a close look a the list above, we can illustrate beneficiaries as the powerless: the ignored and the forgotten of society.

On the opposite side, those who reject the miracles and condemn Jesus:

Jesus’ adversaries

1) the Pharisees, the scribes, the Sadducees, the high priest Caiaphas

2) the elders, the lawyers (Lk. 11:52)

3) the crowds, and the cities (Mt. 8:34, 11:20-24)

4) the merchants in the temple

5) the Roman procurator

This list characterizes the people in political, religious or economic position of power . If we look into this classification more closely, we can detect the whole spectrum of power and hierarchy in society:

the spiritual: the high priest, Sadducees, the Pharisees

the intellectual: the Pharisees, the scribes, the lawyers

the economical: the high priest, the merchants

the political: the Roman procurator, the high priest, the crowd, the Zealots.

Hence the antagonism appears as follows:

established power clusters vs emergent communities

*

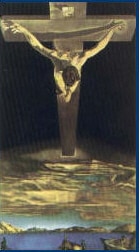

From the beginning, Jesus’ religious authority is questioned by the skeptics, setting apart those who believe and those who reject Jesus Christ. Drawing the boundaries of his Kingdom of God, Jesus’ realm is set up against the worldly powers. The antagonism becomes even more evident as it culminates with his crucifixion. The progression of events that leads to Jesus’ death unfolds quickly. On the cross, except for a few loyal followers, he is abandoned by all.

As the drama unfolds, Jesus gathers numerous followers. At the same time he is confronted by an increasing number of foes. The dividing line between them becomes clearer. His message of love widens the gap between those who believe him and those who reject him. With the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus inaugurates a new law in which love is the only requisite. This new law transcends the old one, which further antagonizes the religious elite of Jerusalem.12

Although the Evangelists take great care in legitimizing Jesus as the Messiah, the priests of Jerusalem question his authority because of his Galilean origin. From the outset Jesus is opposed by the religious authority of the priests and scribes. They are offended by Jesus’ interpretation of the law. Furthermore, he performs miracles freely on the Sabbath, breaking the law. To that effect he answers them: “The Sabbath was made for man, not man for the Sabbath…”.13

But the priests also object to him because the Old Testament warns that only God can perform miracles. Hence, if a prophet performs “signs and wonders” he shall be put to death because the lord is testing the people to see if they are faithful to him.14

But a greater blasphemy than ignoring the Sabbath is the identity of Jesus himself. He declares himself the Son of God, “I and the Father are one”.15

Jn. 8:58 Jesus said to them, “Truly, truly, I say to you, before Abraham was, I am.”

10:34 “Is it not written in your law, `I said, you are gods’?”

Because of this, they want to stone him. Just like they wanted to stone the adulteress that Jesus saved from their hands. They also accuse him of being a demon and a Samaritan. In other words, they associate him with the outcasts, women/prostitutes, the foreigners, and the possessed.

Jesus is accused of being:

blasphemous

possessed by a demon

a Samaritan, a Nazarene, a foreigner

The blasphemies seem to confirm the religious elite’s fears about Jesus. It also justifies their schemes to plot his death. Slowly, behind the scenes, a mischievous consensus is fomenting against him. Like Job, Jesus becomes the target of the political and religious authorities.

Mk. 3:6 The Pharisees went out, and immediately held counsel with the Hero’di-ans against him, how to destroy him. 16

*

He is not only rejected by the elite but by society as a whole.

During his passage in Gadarenes, Jesus is met by two wild demoniacs who ask him to cast their devils out and send them away among the herd of swine that could be seen close by. Jesus complies. As soon as he does, the whole herd is taken by a frenzy and jumps from a cliff into the sea to perish in the water below. With great consternation the herdsmen go to the city to report the event they just witnessed.

Mt. 8:34 And behold, all the city came out to meet Jesus; and when they saw him, they begged him to leave their neighborhood.

Not surprised by this Christ warns his disciple about society and hierarchy.

Jn. 15:18 If the world hates you, know that it has hated me before it hated you. If you were of the world, the world would love its own; but because you are not of the world, but I chose you out of the world, therefore the world hates you.

Did the crowd chase him away because he destroyed the herd, threatening their livelihood? Apparently, the city was not ready to pay the price with their livelihood to save two poor demoniacs.

Even Jerusalem, of all cities, is typified as an example:

Mt. 23:37 “O Jerusalem, Jerusalem, killing the prophets and stoning those who are sent to you!”

Several other cities like Nazareth are mentioned by Jesus as being blind to his message:

Mk. 6:4 “A prophet is not without honor, except in his own country, and among his own kin, and in his own house.”

He goes even further by saying that he has seen more faith in a Roman centurion than in anybody else in Israel. 17

But this, it seems, is only a prelude to what is going to happen later when the whole vengeful crowd in Jerusalem rallies against him and demands his death. The collectivity is seen as having a power of its own, obeying its own laws of inertia. As it turns out, the mob gathered at his trial will be Jesus’ final and fatal foe.

*

The word messiah means the anointed one or the one who is consecrated by anointing for a special function among the people of God. It originally was used to describe the consecration of a king. This ritual was widespread among the cultures of the ancient Near East.18 In Judaism this function is typified by Samuel’s anointing of Saul and later of David as the king of Judah and Israel. Kingship occupied an important place in the theology of Israel. The Davidic era is the golden age of Israel. It is the time when Israel lived at the epitome of its political and religious integrity; when it had complete control over its destiny.

The peace and prosperity of the kingdom of David came to an end with the Assyrian wars (745-721 BCE). The loss of the golden era inspired among its people a longing for a another Messiah. They sought for redeemer, an heir of David, who would bring an end to the misery of foreign conquest. It would enable the people to return from their exile.19

At the root of messianism is the religious and political quest for liberation. In times of great despair, the messianic expectations increase. Messianism became the expression of spiritual consolation for a paradise lost and the hope for the return of past glory.

The pursuit of freedom from foreign influence is at the root of the messianic promise of salvation. Results of recent ethnological studies show that various forms of messianism evolve from a disastrous repercussion of foreign domination and colonialism. The ambiguous feelings of seduction and revulsion toward foreign culture is always coupled by a radical polarization. It imprints ambivalent feelings of lord-victim.

The crisis, propelled by the presence of a foreign culture, threatens the structure of belief from without. Messianism is linked to a perceived threat to the indigenous culture. A fear of loss of religious integrity and collective identity. As a result, the movement revives hopes of messianic salvation that rekindle an idealized past. It instigates a return to these original ideals in their purest form in order to bolster a strong sense of identity. The anxiety provoked by acculturation encourages the radical belief of messianic redemption, often by revolutionary means, which triggers a radical antagonism to the domination of foreign cultures. The rebellion is usually instigated by the elite who perceive the threat as an immediate danger to their own survival. Messianic movements typically nourish mythical expressions of hope. They revert to powerful images of salvation that capture the spirit of the people. The threat of assimilation by the people is then perceived as a personal threat to their own identity and survival.20

The circumstances under which Christ -the Greek equivalent for the word messiah- makes his appearance in Jerusalem are singular. The narratives describe that Jesus accepts the triumphant procession in Jerusalem riding on a donkey like the son of David on Palm Sunday. As we know, his role is not a political one, but that of a spiritual Messiah announcing a kingdom that is not of this world.21

*

Throughout the Gospels, Jesus is determined not to be manipulated by any group. He stands firm on his own unique identity. He refuses to comply to the rules set by the priests. He declines to take up the cause of the nationalist Zealots. As he said, his mission is not of this world. He rejects Satan’s offer to indulge in the riches of the world. And he spurns the idea to exploit his powerful charisma for his personal economic or political gain. He stands firm on his grounds. He declares himself to be the Son of man and the Son of God.

He applies the same determination to his fate. He knows about his oncoming death. But he will not try to change the course of destiny, though he could at any time.

At his arrest, one after the other, his disciples abandon him to his captors. Apparently, they thought Jesus to be someone else:

Lk. 24:21 …we had hoped that he was the one to redeem Israel.

When Jesus is betrayed by Judas, he is brought in front of the Sanhedrin where he is finally confronted by his adversaries.22

Caiaphas, the Sadducee high priest, is present among the crowd of Pharisees and scribes who have already decided on Jesus’ death. But they have a problem: they must find a way to inculpate him. At his interrogation, Jesus is questioned about his identity. He is asked if he is the Son of God, he replies that he is. He also answers them that he is the Son of man who will be at the right hand of the Power.

Upon his reply, they accuse him of blasphemy and condemn him to death. Shortly after, Jesus is sent to the procurator Pilate, in whose hands rests the political and legal authority over these matters. He states to Jesus that he is being accused by the religious elite of fomenting a revolt against Rome by telling the people not to pay their taxes. He is also accused of proclaiming himself Christ, a king. To his questions Jesus replies:

Jn. 18:36 “My kingship is not of this world; if my kingship were of this world, my servants would fight, that I might not be handed over to the Jews; but my kingship is not from the world.” Pilate said to him, “So you are a king?” Jesus answered, “You say that I am a king. For this I was born, and for this I have come into the world, to bear witness to the truth. Every one who is of the truth hears my voice.” Pilate said to him, “What is truth?”

Seeing nothing wrong with Jesus, Pilate turns to the crowd and he asks them if they want to release Jesus, since it is a custom to free a prisoner during the Passover. Yet the mob demands that Barabbas, a known thief and probably a revolutionary, be released instead.

Here the parallel between Christ’s judgment and the sacrificial ritual in Leviticus 16 is compelling. The Old Testament text describes the directives for the Mosaic ritual of the Day of Atonement; to take among the flocks belonging to the people, two male goats. One to be chosen to be sacrificed as a sin-offering to Yahweh, the other as an atonement for Israel’s sins and to be set free in the wilderness as an offering to Azazel, the sins of the people having been symbolically laid upon it. Azazel is the name given to a being who opposes Yahweh. The Vulgate version of the Bible rendered the word Azazel into caper emissarius.23 Later, Luther translated the word into lediger bock meaning literally free-goat. Finally, the word was rendered into English as scapegoat: a victim who is innocently blamed or punished for the sins of others.24

The parallel suggests that Jesus is depicted as a human offering to Yahweh. While Barabbas -the name means son of the father– who is symbolized as carrying the sins of Israel, is set free to the foreign lands.

The crowds that chased him away are now gathered in Jerusalem to demand his death. They choose Barabbas rather than Christ. Jesus who promises the kingdom of God to the powerless is a danger to the established order of society. And Caiaphas, as its spokesman, explains why Christ should die:

Jn. 11:50 “You know nothing at all; you do not understand that it is expedient for you that one man should die for the people, and that the whole nation should not perish.”

It is better to sacrifice one person for the sake of the whole society. They perpetuate the false belief that a scapegoat will solve all their problems. Jesus becomes a pharmakos, the individual kept by the Greek community as a scapegoat to sacrifice in times of social crisis. But history shows that violence begets violence. The words spoken by Caiaphas are empty words since the temple and Jerusalem will finally be destroyed in 70 CE anyhow. Yet another reason why they seek his death stems from the power of his word. They think he is fomenting political and religious upheaval. They fear he is seeking to abrogate their power.

But Jesus’ prophetic words echo an ultimate truth when he adds:

Lk. 23:34 “Father, forgive them; for they know not what they do.”

Jesus’ crucifixion underlines the illusion of violence. Sacrifice and love are the only ways for human salvation.25

Although Jesus may be innocent of the crimes he is accused of, he is certainly not a victim. He freely agrees to his fate. He knows and understands the full extent of his decision. His consent is a crucial act of free will. He like Job, as an individual, is left alone against all the prejudice and powers of this world. He knows that the powers invested in the political, the social, the economical, and the religious, are present like a dark cloud over him. Jesus knows he has to endure his death so that his absence could be effective. So that his meaningful presence on earth may be resurrected by faith. Only then, can he be of benefit to all. Consequently, he tells his apostles that he must leave in order for his message to be fully understood:

Jn. 16:7 Nevertheless I tell you the truth: it is to your advantage that I go away.

Only then will they understand that he is the message of hope for the powerless as the beneficiaries of his kingdom, and not those who already control the powers in their own world.

Mt. 22:16 “Teacher, we know that you are true, and teach the way of God truthfully, and care for no man; for you do not regard the position of men.”

They know that the power of the word of God is stronger than any human institution. But Jesus clearly did not entice political and economical upheaval. He took great care to share the urgency of the message of love. He introduced a new law to replace the old. He inaugurated a kingdom where women, children, the poor, the sick, the outcasts, the handicapped, the estranged, the mentally disturbed, the alien, the stranger, and the slave, all have equal access to his kingdom.

*

Jesus Christ’s death might appear as an obstacle to his ongoing mission. A timely and tragic obstruction. Far from the truth. His death is precursory to an even greater medium for his message. While on earth he communicated the word of God to the people around him, after his death Jesus embodies a new role in his resurrected body. The risen Christ becomes the ultimate and eternal medium for his message, a personal image to which all have access.

Doctrines about death and resurrection have evolved and changed in the Old Testament. According to the Bible, man is not a being composed of a body and a soul but of a soul with the vitality of the flesh. There is no duality between body and soul. Man becomes a soul when he is born, and when he dies he is a dead soul. His soul comes directly from God.26 The word soul in Hebrew means literally a living being, an animated body. Consequently, the dead in Sheol are not the soul of the dead but shadows of beings. Accordingly, they are considered powerless and weak.27 They could not come back to life.

Job 7:9 …he who goes down to Sheol does not come up;

Eccles. 3:19 For the fate of the sons of men and the fate of beasts is the same; as one dies, so dies the other.

The concept evolved and became closely associated with the idea of the restoration of Israel. Particularly in times of historical distress. In Ezechiel, the resurrection of the dead bones did not imply a return from Sheol, but a return of the nation from the dead condition of exile.28

Further development of the concept occurred during the period of the Maccabeans where the belief in the resurrection is clearly expressed:

Dan. 12:2 And many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt.

Later, the chief proponents of the resurrection were the Pharisees. The resurrection was applicable only to a select few like Moses, David, and to the more pious elite of their congregation.

In Christianity, the resurrection of the body became the cornerstone of its faith.

*

The Gospels share basically the same material in respect to the discovery of the empty tomb by a group of women.29 In all of the accounts, the central figure is a woman called Mary Magdalene. She is Jesus’ loved one. She is the first person who perceives the resurrected body of Christ.

Her name is revealing. Mary was from Magdala -hence Magdalene- a city situated on the west bank of the Sea of Galilee, about 20 km north of Nazareth. The word also means tower or fortress.30

But what is most peculiar is the time at which she gains more prominence in the Gospels. The narrative recounts the presence of this group of women who have been following Jesus during the greater part of his public life but who have been overshadowed by the more predominant group of male disciples. Only here, and at a very crucial moment, are the women finally recognized as followers in the same manner as their male counterparts.31

We would like to introduce at this point the role of the metaphor in terms of symbolic significance:

John 10:9 I am the door ─gate

John 14:6 I am the way

It might be implied that Jesus uses the metaphor to reveal his message.

Mat 16:18 You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my community ─Church

Jesus tells Simon that he is a rock ─peter literally means rock─ and he will be known as the rock on which Jesus will build his community.

The last supper is where Jesus shares his last meal, breaks the bread and drinks from the sacred cup. The scene is the center of the whole Catholic faith. And the Eucharist is a sacrament that faithful Catholics partake in Church with the holy communion. At the Last Supper Jesus shares the bread and wine with his apostles and says these words.

Mark 14: 22-24 This is my body…This is my blood

The metaphor is a figure of speech that implies a shift in meaning and a spiritual code. A break in the normal use of language. Simultaneously breaking with the normal social conventions and religious practices. Simply put, the metaphorical interpretation of the Gospels could be considered as a keystone behind the last supper. What the cup holds is not wine but the metaphorical sacrificial blood.

Furthermore, if Simon is the metaphorical the rock on which Jesus will build his Church, then Mary of Magdala, who was the first to witness the risen Lord, is to be considered the tower that will be built on that rock ─foundation. In addition, the name Madgal-eder also appears in Micah (4:8-10) and refers symbolically to a tower or stronghold of the flock. Mary Magdalene then, will stand on the rock as the stronghold for all future Christian communities.

The account also refers to the angels that appear to both male and female apostles. The apparition is also paralleled to the annunciation. Jesus’ birth in Mary’s womb is the counterpart to Mary’s presence in front of the empty tomb. Birth and death are privileged symbols of life and regeneration. Here, they become kindred to the resurrection of Christ.

Christ’s death also signifies the sudden emptiness in the followers’ lives. The physical absence of their Master leaves them powerless and lost. Yet as soon as the news of the empty tomb reaches them, they are filled with hope.

The message from the angels fulfills the prediction about his return:

Hos. 6:2 After two days he will revive us; on the third day he will raise us up, that we may live before him.

Jesus is the bodily proof that God is accessible to us as a person. It is as a person that he was able to establish relationships with his followers. He became the Word in order to communicate his will directly to the world.

With his resurrected body Jesus becomes the medium par excellence. His death is no longer an obstacle to his ongoing message. With his risen body Christ’s message is not limited by the boundaries of time or space. Although his death abruptly ends his physical presence on earth, the heavenly body is eternally present, accessible to all at all times.

Jesus’ resurrected body, however, is not the restoration of a previous condition in the flesh, but a transformation of a radical kind. Not to be confused with the decaying nature of the physical body. Christ’s resurrection is not a return to a former condition, but the passage to a totally new one. With his new condition he is given the title of Lord. A sovereign state free from the tyranny of the powers of the world that have persecuted, condemned and crucified Jesus. And as stated in Encyclical letter Mystici Corporis by Pius XII, the Church, or the assembly of believers, is the Body of Christ.

Paul in 1 Corinthians distinguishes the physical body from the spiritual body. The first is a body and mortal, the second has a body but is spiritual. He also correlates the body to the idea of image. Both are related to the identifiable essence of Jesus Christ.

1 Cor 15:49 Just as we have borne the image of the man of dust, we shall also bear the image of the man of heaven.

The image of this identifiable body is no longer indistinguishable among the crowd but lives above us, in heaven. His resurrected body becomes the mark of a new spiritual identity. And through his Ascension Jesus Christ, in his heavenly body, rises to the full view of all. It becomes the ultimate miracle, the greatest of all visible signs.

That he has risen from the dead is a victory over the state of remaining in the shadow of nothingness. Therefore, the former condition of the dead, described as the meaningless state of the shadows of the powerless, is transcended with the resurrection.

The presence of the angel standing outside the tomb is further evidence of the good news about Christ’s heavenly condition. The angels, from the Hebrew mal’akh which means messenger, are an additional link to the Old Testament. The angels were messengers of the Lord to Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, and Moses.32 Similarly, the angel becomes the medium of Christ the Lord to his followers.

*

Like Job, he was abandoned by all, even God. Defender of the outcasts, he dies like one himself. Both typify the innocent servant who suffers for the sake of truth. Job’s suffering enables him to see God, while Jesus dies to be with God.

Jesus Christ is the prototype of a new humanity.

Like Job, he is a scapegoat singled out by society. This isolation enables Job to have a vision of God he could not conceive before. On the other hand, Jesus is God because he gave his life for that truth. Love and knowledge about God is now accessible through him. His resurrected body is a visible sign, the door to his realm. It enables the powerless to have access to the power of God despite the entrenched powers of the world.

Although Jesus is loved by many, his adversaries are plenty. At the end, they overcome him. Even though he chastised the hypocrisy of the Pharisees, he did not condemn their religion. As much as he opposed the merchants in the temple, he did not oppose commerce. He complained about the unfaithfulness of the cities, but he did not repudiate social order. He simply proclaimed that the powers of this world have no jurisdiction over his realm. His people obey a different set of laws and are governed by the power of love.

Jn. 13:13 You call me Teacher and Lord; and you are right, for so I am. If I then, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have given you an example, that you also should do as I have done to you. Truly, truly, I say to you, a servant is not greater than his master; nor is he who is sent greater than he who sent him.

The real purpose of the miracle of the resurrection relies on teaching the message of love thy neighbor to all nations to be part of the Mystical Body of Christ; the Church.

Mt. 28:18 And Jesus came and said to them, “All authority in heaven and on earth has been given to me. Go therefore and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit, teaching them to observe all that I have commanded you; and lo, I am with you always, to the close of the age.”

_______________

1 Isa. 40:9; 52:7; 61:1; etc.

2 Paul Feine, Johannes Behm, and reedited by Werner Georg Kummel, Introduction to the New Testament, New York, Abington Press, 1966.

3 Mt. 1:1-16; Gen. 5:1-31; 10:1-32; 11:10-31.

4 The second explanation, made popular by Luther, interprets the inclusion of these four women as the symbolic presence of foreigners -Gentiles or persons associated with Gentiles in Bethshibah’s case- in God’s plan.

5 Raymond E. Brown, The Birth of the Messiah, New York, Images Books, 1979.

6 Emil Schurer, A History of the Jewish People in the Time of Jesus, New York, Schocken Books, 1971.

7 F. F. Bruce, Israel And The Nations, Grand Rapids, Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1963.

8 In the New Testament the Pharisees are also identified as the scribes and the sages; Mat. 2:4; 21:15; 23:15. See Ellis Rivkin, What Crucified Jesus?, London, SCM Press Ltd, 1986.

9 J. T. Maertens, La Structure des Récits de Miracles dans les Synoptiques, in, Sciences Religieuses/ Religious Studies, 6/3, (1976-77), 253-266.

10 The young woman can also be rendered into “virgin”.

11 Deut. 13:1-11.

12 Mt. 5:1-48; Lk. 6:20-49.

13 Mk. 2:27.

14 Deut. 13:1-13.

15 Jn. 10:30.

16 The Herodians were political functionaries influential in the court of Herod Antipas.

17 Mt. 8:10.

18 In Is. 45:1, the persian king Cyrus is addressed by Yahweh as “his anointed”. See also; Jg. 9:8,15; 1 Sam. 10:1, 2Sam. 2:4; 5:3.

19 Is. 9:1-6; 2 Sam. 7:16; Is. 55:3-5.

20 The Islamic Revolution in Iran is a case in point. Here are some additional references on messianism: W. Muhlmann, Messianismes Révolutionnaires du Tièrs-Monde, Paris, Gallimard, 1968; G. Devereux, Ethnopsychanalyse Complémentariste, Paris, Flamarion, 1972, and by the same author, Essais D’Ethnopsychiatrie Générale, Paris, Gallimard, 1970; also the interesting book by, F. Laplantine, L’Ethnopsychiatrie, Paris, Editions Universitaires, Paris, 1973, and his other work, Les Trois Voix de l’Imaginaire, Paris, Editions Universitaires, 1974.

21 Mk. 14: 61-65; Dan. 7:13.

22 There is a parallel here between Judas his disciple and the historical Judas the Galilean, the notorious nationalist.

23 René Girard, The Scapegoat, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986.

24 The Tindale Oxford Dictionary.

25 “In future, all violence will reveal what Christ’s Passion revealed, the foolish genesis of bloodstained idols and the false gods of religion, politics, and ideologies. The murderers remain convinced of the worthiness of their sacrifices. They, too, know not what they do and we must forgive them. The time has come for us to forgive one another. If we wait any longer there will not be time enough”. In Rene Girard’s, The Scapegoat, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986, 212.

26 Gen. 2:7; Num. 23:10.

27 Isa. 14:9-11; 26:14; Ps. 88; Job 26:5.

28 Ezek. 37:1-14.

29 The message is directed to Mary who is described in the narrative as the woman from whom Jesus had cast out seven demons (Lk. 8:2). We can make another parallel with Proverbs 9:13-18 where the dead condition and the crazy woman may be linked here with Mary Magdalene.

30 Jean Daniélou, La Résurrection, Paris, Seuil, 1969, 11.

31 Lk. 8:2-4; Mk. 15:40-41.

32 Gen. 18:1; 24:7; 31:11; Ex. 3:2.