Michel A Rizzotti

The Book of Job tells the story of an upright man whose integrity is put to the test. The hero is chastised and tormented for no apparent reason. All along, he insists on his innocence and pleads for justice. Job is temporarily alienated from his God and undertakes a journey into the profane where he is totally segregated from the world. But before he is finally restored to a greater glory, he becomes the outcast of outcasts. He is the innocent victim repudiated by the whole society. The narrative is an excursion into the unknown. It discloses a revelation of God.

the setting………. the land of Uz

the hero…………..Job

the quest………….justice

the obstacle……..Satan

the mentor……….Job’s integrity

the outcome……..a vision of God

The “Book of Job” is called Iyyov in Hebrew. The etymology of the word may have meant originally “enemy”, while a similar Arabic root signifies “the penitent”. The form and themes of the narrative are closely similar to the Babylonian wisdom writings of the “Poem of the Righteous Sufferer” -XIVth century BC-. The “Acrostic Dialogue on Theodicy” -IXth century BC-. It also bears some resemblance to the Egyptian texts called “The Complaints of the Eloquent Peasant” and “Dialogue of the Man Weary of his Life and Soul”, both written between the XXth and the XVIIIth century BC. The author is unknown. The date of the book is uncertain, but popular consensus points to dates ranging between 600-400 BC. Job is a man from the land of Uz, a place somewhere at the edge of the desert, in the south-eastern parts of the Dead Sea; probably a city of ancient Edom.

The “Book of Job” is called Iyyov in Hebrew. The etymology of the word may have meant originally “enemy”, while a similar Arabic root signifies “the penitent”. The form and themes of the narrative are closely similar to the Babylonian wisdom writings of the “Poem of the Righteous Sufferer” -XIVth century BC-. The “Acrostic Dialogue on Theodicy” -IXth century BC-. It also bears some resemblance to the Egyptian texts called “The Complaints of the Eloquent Peasant” and “Dialogue of the Man Weary of his Life and Soul”, both written between the XXth and the XVIIIth century BC. The author is unknown. The date of the book is uncertain, but popular consensus points to dates ranging between 600-400 BC. Job is a man from the land of Uz, a place somewhere at the edge of the desert, in the south-eastern parts of the Dead Sea; probably a city of ancient Edom.

The central theme of the narrative is set on the theological debate about God’s divine right not to justify his actions to “man”. His authority is enough of a prerogative to sanction any of his deeds. And, no matter how unjust his actions may appear, they should not be questioned by man since God is God.

Job is not an Israelite; he is depicted in the narrative as a foreigner. His life is described as being exemplar. We might say that he is a perfect mythical model:

Job 1:8 “Have you considered my servant Job, that there is none like him on the earth…”

His life is blessed with numerous children, and he is surrounded by many loyal servants. His wealth is measurably abundant with cattle.

Job 1:3 …this man was the greatest of all the people of the east.

Nevertheless, Job is unaware that in the highest courts his integrity is being questioned and his livelihood is at stake.

One day, the sons of God appear at His court accompanied by a stranger. Curious about the newcomer, God asks him of his whereabouts. Satan, without being specific, replies that he roamed the earth. God must have presumed the intruder wise since he questions him about Job’s righteousness. Satan’s response is that Job has no merit for his probity since he has been favored by the Lord’s grace. God, to prove Satan’s allegations wrong, allows Job to be put to a test. As a result, Job loses his wealth and his children die. Job is distraught, but he remains loyal to his God. His character remains intact. Unfortunately, Satan does not give up. He returns a second time and insists that Job will curse God’s name if he takes his good health away. Again, the Lord allows the fiend to inflict a terrible disease on Job:

Job 2:7…loathsome sores from the sole of his foot to the crown of his head.

Overtaken by his affliction, Job admits having sinned in his life but proclaims that his punishment is outrageously disproportionate to his offense. Despite the calamities that befall him, he refuses to curse his God. He even remains steadfast against his wife’s incessant plea to damn his creator for his unjust treatment. Despite all, Job remains true to his Lord. But when a group of his friends come to deplore his condition, Job’s willpower begins to falter. He finally curses the day that he was born. The long series of dialogues and lamentations begin. His friends, instead of lending their support, condemn him. They maintain that he must be guilty to deserve such a fate, since God is just.

Before his ordeal, Job was living content unaware that God was willing to forsake him in order to test his integrity. As the calamities befall him one after the other, our hero cries for justice, unaware of what his dreadful experience is about to reveal.

Contrary to Genesis, where the serpent entices the woman to challenge God’s command, the narrative presents Satan as the one who defies the Lord to test Job’s integrity. Satan is presented as a symbol of wisdom, since he has roamed the earth, and God is curious to know his opinion about his prized servant. Nothing is said about the alien except that he is not one of God’s sons. Etymologically, the word Satan in Hebrew means adversary. It is synonymous with accuser or prosecutor (1). It also entails one who takes up an antagonistic position against somebody; ie, an enemy (2). What follows is perplexing. God forsakes his favorite servant at the suggestion made by a stranger. As a result, Job becomes a scapegoat of God’s inscrutable design.

As the afflictions haunt our hero, everybody, from the highest rank to the lowest cast, begins to avoid and shun him. Plagued by a horrible disease and bad breath, his wife also finds him repulsive. Even his servants treat him as a stranger. Children everywhere despise him. His intimate friends abhor him. He is even reviled by the outcasts of the community. He is singled out as a scapegoat and totally excluded from society. God’s favorite servant has become a pariah rejected by the whole community.

His friends, instead of consoling him, ask him to repent for his sins, since God rewards the just and punishes the guilty. Therefore, Job should repent.

Such is the subject of all the dialogues between Job and his friends Eliphaz, Bildad, Zophar, and Elihu. They symbolize the “order” in society. They, like Job before his downfall, are all representatives of the hierarchy, they are delegates of the status quo. They rally to God’s side to preserve the order of which they are a part. They hold on to the belief that God rewards the righteous by giving him wealth and power, alternatively punishing the sinner by taking away his riches and making him an outcast. God is an ally of the strong. He selects the upright and blameless and segregates the offender.

Their biggest fear, it seems, is that the hero’s downfall might portend their own demise if they don’t sanction God’s condemnation. Therefore, like a contagious disease, he must be quarantined. As a result, the process of collective victimization begins. It is focused on a sole victim: the scapegoat. As they all rally to God’s decision, Job is singled out to safeguard against the divine wrath. The ostracism becomes in effect a “violent” process of social segregation. Not only Job’s friends but all the members of the community behave in a “mimical” fashion. They aggregate into a dynamic entity -a “mob”- whose sole purpose is to foment a consensus against their chosen victim and exclude him from their ranks. Job is chosen precisely as the scapegoat for an ultimate purpose: to defend the order and hierarchy of society which the victim is believed to be threatening. (3)

Yet it is the complete exclusion from society that enables Job to experience his revelation. It allows him to perceive the whole reality of God and of the community from which he becomes excluded. Because he is segregated, he sees social reality as an outsider. He perceives the whole structure of the society from without.

As the hero finally survives his ordeal, he is reinstated with greater power and glory than he previously had. The mythological significance disclosed in the account is central: the dynamic interaction between the hero, as an individual, and God and society becomes the foundation of the revelation. (4) It goes without saying that the journey is an arduous one. Similar, in some respects, to Israel’s experience in the desert: a trek into the unknown. And although Satan is depicted as the obstacle, he nevertheless plays a primordial part in the development of the hero’s apperception of God.

*

Even though the process of victimization is painful for Job, it is necessary in order for him to see God. To this effect the mentor is Job’s integrity itself. His trial shows how his personal righteousness is essential to the final outcome. It enables him to transcend his perception of God’s reality. Job’s wisdom allows him to recognize that his personal rectitude is not justifiable in the face of God. God’s authority, albeit a questionable one, is still a divine prerogative. God has a theological precedence over humans, and Job is no exception no matter how righteous he is.

The text describes him as “blameless” and “upright”, he fears God and turns away from evil. His integrity, however, does not imply that he is sinless. His uprightness is used in the sense of his perfect integration into the community and with the environment rather than his being without sin. Furthermore, Job’s integrity implies that his personality is whole and that he is at peace with himself and with his community. His relationships are of the “right” kind with his family, and with his God. This righteousness translates itself into peace –shalom– and well being.

This quality is in turn transmitted to his progeny. His sense of responsibility is such that he even performs atonement for his sons in anticipation that they might commit blasphemy. Job’s piety is only matched by his virtue. In the Book of Job, adversity meets integrity head on and integrity is not subdued.

*

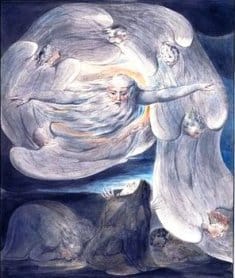

We have already outlined that the denouement is revealed in terms of a vision of God. The journey reveals what is at the core of the religious experience. (5)

The focal point in any definition of religion revolves around the nature and function of the sacred. It is the matrix of any religious phenomenon whatever its cultural or historical origin. Emile Durkheim showed the importance of the dichotomy between the sacred and the profane.(6) The sacred generates a field of belief unto itself which is best defined in terms of conviction. Nothing in particular is sacred yet anything can be sacred. It all depends on the historical or the spatio-temporal circumstances under which a certain phenomenon becomes sacrosanct. That is what is referred to as a hierophany: namely, when the sacred manifests itself in history as typified by Yahweh and the burning bush. And when the sacred appears, it automatically imposes an arbitrary distance to the profane, which it opposes.

sacred vs profane

“holy ground” vs the common ground

Yahweh vs the other gods

the center vs the outside

Normally, God is the Holy One. Yet, in the narrative, he shares his sacredness with his favorite servant. As Satan explains,

Job 1:10 “Have you not put a hedge around him…on every side?”

In other words, Job has been overwhelmingly protected and favored by God. He has been put at the center of God’s holy embrace. The sacred claims the supremacy of attention. It also attempts to circumscribe a reality, more precisely, an identity. And this identity is maintained by its opposition to the profane. The sacred is by definition that which is distinct from the profane. However, the profane is a religious reality necessary to the sacred, since the sacred is sacred precisely because of its opposition to the profane. Satan, as the adversary, illustrates very well what we mean. Satan is Satan because he instigates the conflict between God and Job. He separates the holy union between the lord and his servant, propelling Job into the realm of the profane where he is excluded from everything.

The following illustrates how the profane plays a critical role in the edification of the sacred:

holy/sacred vs common/profane

Moses/Israel vs Pharaoh/Egypt

Yahweh vs the other gods

As noted by Mircea Eliade, the dynamic relation between the sacred and the profane demonstrates that anything can be consecrated.(6) It is not specific persons or things that have sacred values per se, it is because they are recognized as such at some crucial moment in time. The epiphany of the burning bush, for instance, has been consecrated by the narrative as the ultimate revelation of Yahweh and has been acknowledged as such by the people of Israel. The sacred always imposes a separation and a distance between its center, depicted as holy, and the profane, located outside its periphery. Hence, the profane, which lies beyond the consecrated field, is depicted as the excluded and the alien. The dichotomy between these two principles is an essential one. Just think of the division between:

sacred vs profane

God/good vs Satan/evil

Jews vs gentiles

Christians vs the heathen/pagan

Muslims vs the infidels

Furthermore, all religious creeds underline an opposition to the outside world defined as the profane. Our world is meaningful, while the other world is chaotic and mostly inhabited with strangers also described as demons.(7) As outlined in the Book of Job, Satan is a foreigner and an alien.

Literally the word profane means “that which is outside the temple”. The profane refers to whatever lies beyond the boundaries of the sacred. This explains why the profane is never cited in clear terms. By definition, the outside world is always other: a blurred reality always inhabited by unknown and strange beings. As such, it is perceived as a threat to the vivid reality of the sacred to which we identify. Yet this other reality is threatening precisely because it presents an-other sacred reality of its own that challenges the exclusivity of our beliefs. In other words, this other reality defies the foundation of the exclusive validity of our sacred beliefs. Therefore, our beliefs are defined as sacred and are opposed to other beliefs described as alien which are ruled by other gods. Our mythical cosmos confines us to recognize only our world as sacred and discard the rest as profane.

Religion generates its sacred identity from the myths and rituals that perpetuate the creed regulated by the hierarchy of priests. The closer one is to the “holy”, the greater the sense of sacredness. Hence, the antagonism amplifies the identities of the sacred and the profane. The stronger the opposition the stronger the belief in the sacred.

sacred vs profane

believers vs unbelievers

theists vs atheists

civilized vs primitive

Belief is generated by the dynamic opposition between the two principles. As the Bible shows, the God of the fathers must be protected against the intrusion of other gods that might challenge His supremacy. Therefore, we always acknowledge the sacred validity of our own religious beliefs but deny it to others. This is one of the reasons why the profane is always excluded from the sacred. Because it challenges the foundation of the absolute validity of the sacred and it shatters the conviction in the religious uniqueness of the sacred and its tenets. To protect this supremacy, the sacred precipitates the dynamic opposition to keep the profane at a distance. This is why the essence of faith lies in antagonism:

Gen. 32:28 “Your name shall no more be called Jacob, but Israel, for you have striven with God and with men, and have prevailed.”

We find this dichotomy in each and every religion. What is viewed as sacred is opposed to the profane which in turn has a sacred validity of its own. In other words, the sacred seeks to be exclusive while denigrating the profane’s own sacred validity.

*

Job has been described as “the greatest of all people in the east”, protected by God’s grace and surrounded by his sacred embrace. As the story unfolds, we witness Job’s downfall. Originally at the center of attention, he becomes more and more alienated from God and the community. As he becomes excluded, he is also debased. The hero is singled out as victim and scapegoat. Finally, he is isolated from the very society in which he was a central figure.

As Job loses everything, he is further segregated into the realm of the profane. Formerly at the center of God’s favor, he now stands isolated from everybody, outside of the Lord’s reach. As such, he lives the life of a total outcast. He becomes the prototype of a lord-victim.

Job 3:20 “Why is light given to him that is in misery,

and life to the bitter in soul,

who long for death, but it comes not,

and dig for it more than for hid treasures;”

*

Closely related to the sacred and the profane is a third concept which is essential to the whole dynamic religious experience. This principle is the wholly other. (8) The term wholly is derived from the word “whole”, meaning entirely, in full, throughout. Used in conjunction with the word other, it becomes a category in which the two distinct entities of the sacred and profane inter-activate and transcend one another.

The dynamic aspect of the wholly other reveals its infinite nature. Its scope is to transcend all cultural and religious boundaries into the all inclusive. The wholly other stems from the antagonism of the sacred and profane reality. It transcends the sacred’s own exclusivity by opening up to the profane into the all inclusive dynamic truth. As we saw, Job lived through both realities: the sacred and the profane. Hence, the wholly other transcends one state of religious reality into another. In other words, it is Job’s transition from the sacred to the profane reality that underlines the fundamental essence of the wholly other. It is his experience of being both included and excluded from the sacred that allows Job to see the whole reality of God: the sacred and the profane. Surprisingly, it is through the profane that Job has a glimpse of the whole and other nature of the divine reality. Step by step, as he moves away from the sacred into the profane, he experiences the all inclusive. His apperception of the whole becomes in effect a revelation of God.

the wholly other

sacred vs profane

The prologue describes a special relationship between God and Job. Similar to Genesis, it is disturbed by the arrival of an alien: the serpent in Genesis, and Satan in Job. As the account reveals, Job is abandoned by God for the sake of the adversary. The special relationship between God and his servant is broken. By the same token an order is broken and Job is precipitated into the unknown.

At the end of the narrative Job is reinstated into God’s favor. God restores everything Job had lost and much more. Job doubles his wealth. Family and friends return. He has many other children. As Job’s innocence is vindicated, he nevertheless submits to the theological premise that God transcends any human prerogative, as he confesses:

Job 42:5 “I knew you then by hearsay;

but now, having seen you with my own eyes,

I retract all I have said

and in dust and ashes I repent.”

In a final remorseful outburst, he recognizes his own mortality and bows to God’s immortality. He yields to God’s eternal prerogative.

To conclude, our hero has temporarily lived the demeaning journey of being excluded from God and community. This profane experience of Job is related to seeing the workings of the hierarchical order of which he was part. Because he belonged to that sacred order, he only temporarily sojourns into the realm of the profane. Time enough to see the “whole” reality of God, and only to reemerge with greater glory. Resulting in the revelation of having “seen” the whole reality of God: the sacred, the profane and the wholly other.

From the same author:

The Risen Lord: On Sovereignty and Tyranny

___________

1 Zech. 3:1-5 and I Chr. 21:1. Paul in Romans 16:20, equates the serpent of Genesis to the Satan of Job. The reptile, symbol of the Goddess and fertility in the creation myth, is held responsible in Job for the alienation between God and “man”.

2 The Arabic verb for “Shatana” also means “to be remote”, especially from the truth of God.

3 See Rene Girard, Job: the Victim of his People, London, Athlone Press, 1967, and his other work, The Scapegoat, Chicago, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1986. See also the interesting analysis made by Dabrowski Kazimierz about desintegration, in, Positive Desintegration, Boston, Little, Brown, 1964.

4 As Rene Girard puts it “religion is in itself culture” Ibid. Job, 152.

5 This experience is recounted in myth, yet it is only an expression of the experience, and it must be differentiated from the religious experience itself, which is unique and unfathomable and cannot be properly described in words because they convey only a glimpse of the religious experience. Consequently, we can only rely on the language that relates that experience.

6 Emile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, New York, Free Press, 1965 and Rudolf Otto, in, The Idea of the Holy, London, Oxford University Press, 1958.

7 Mircea Eliade, The Sacred and the Profane, New York, Harper & Row, 1959.

8 Roger Caillois, L’Homme et le Sacre, Paris, Gallimard, 1939, 35-59.

9 Rudolph Otto, Ibid, 25.

I am in press with on your blog and the knowledge of the old testament.

Yes job a great testament of faith strength and wiliness he experience great trial but did not curse God as his wife subject wish would have been a bad choice.

Forever in his present Morning Star

I see many eisogetic interpretations of Job understandably because it is such a difficult book to interpret. It has a number of interesting characteristics

1) Satan permission to enter the heavenly presence of God

2) There is a curious prescriptive dialogue between God and Satan at the introduction to each meeting

3) Cursing God seems to be a major theme running through the book. a) Job makes religious offerings to God in case his children have cursed God in their hearts b) Satan is sure Job will curse God if God\’s hedge of protection is removed from Job c) Job\’s wife suggests Job \”curse God and die\” as a result of Job\’s own cursed life d) it is emphasized that after all that Job suffered at the permission of God, he did not curse God.

4) It seems that God initiates the whole process asking Satan if he has \”considered Job…\”, which it seems Satan has. Satan already indicates he knows Job leads a God-charmed life.

5) God however accuses Satan of inciting God against Job after it seems God Himself has incited Satan against Job in the first meeting.

6) Elihu (God\’s righteous intercessor) seems to clarify that Job\’s self justifying pride has become the problem Job assumes he knows enough about what is going on than he does or even should. We are made aware of more than Job is made aware since we are given the peek into the heavenly dialogue between God and Satan. We still are not given a full explanation as to why except for the test hypothesis. Does Job \”fear God for nothing\”?

7) God puts a strange and unexpected emphasis on a \”Leviathan\” creature at the end of His closing rebuke to Job. \”He beholds every high thing; He is king over all the children of pride\”

Summary possibilities:

1) Do we fear God only when we receive His blessing and benefits (or threat of or actual punishment)? Will we curse or ignore Him otherwise

2) Is our fundamental sin problem self righteous and/or self justifying pride?

3) Do we need to accept God\’s sovereign actions and decisions unconditionally and refrain from judgement of God? Do we need to understanding that some actions and decisions of God appear unfair, unjust or contradictory due to our ignorance rather than God being unfair, unjust or contradictory?

We simply need to trust God unconditionally in All circumstances

\”For we know that God is working all things together for good for those who love him and are called according to His purposes\” Romans 8:28